Strategy in the Family Firm: The Importance of Strategic Thinking

A UNC Kenan-Flagler Family Enterprise Center White Paper

by Stephen P. Miller

Copyright 2020. For reprint permission, contact fec@unc.edu

|

|

INTRODUCTION

When we survey family business leaders, we often find that they want to learn more about strategy. While many family firms have strategic plans, those plans often lack a clear expression of an overall competitive strategy that reflects deep strategic thinking. Clearly identifying and committing to an overall competitive strategy and executing on that strategy is central to achieving business and family goals, company profitability, and the long-term survival of the business.

This paper defines strategic thinking, emphasizes the importance of organizational culture in executing strategy, and provides two examples of family firms with powerful competitive strategies in very different industries. It also identifies some of the ways strategy in a family enterprise differs from strategy in a non-family firm and out- lines a simple method for incorporating strategic thinking into an effective strategic plan.

STRATEGIC THINKING

Strategic thinking is about deciding how to compete in the marketplace. It is getting crystal clear about why a customer would choose to buy a family firm’s products or services instead of a competitor’s. In his classic article “What is Strategy,” Michael Porter defines strategy as “a company’s distinctive approach to competing and the competitive advantages on which it will be based” (Porter, 1996). He identifies three generic strategies: cost leadership, differentiation, and focus (Porter, 1998).

Companies that choose cost leadership as their overall strategy compete by offering lower prices than their competitors. Walmart is a good example of a company that strives to offer the lowest prices on a wide variety of merchandise and for a broad range of customers. Successfully pursuing a cost leadership strategy usually requires scale and a relentless effort to reduce costs.

Companies that pursue a differentiation strategy strive to create products and services that customers perceive as different in some way from those offered by competitors. Apple is a good example of a differentiator. Apple competes through innovation, design, and branding, and targets a relatively broad range of customers who are willing to pay a higher price for Apple technology. Successfully pursuing a differentiation strategy requires a deep understanding of customers’ needs and wants and their willingness to pay more for those preferences, and then investing in creating, producing, and delivering products and services that deliver value to those customers.

Companies that pursue a focused strategy target a specific set of customers, geographic region, or segmented product or service category. The strategy could be a focused low-cost strategy, a focused differentiated strategy, or both. While other, often larger, firms seek to compete across an entire industry, companies that adopt a focused strategy target a narrower segment of the market. Most of the family firms we know pursue some variation of a focused strategy.

An excellent example of a company that has adopted a focused differentiated strategy that is low cost for some customers and value add for others is Aldridge Electric (https://www.aldridge- group.com), a third-generation family business headquartered in Libertyville, Illinois. Aldridge is led by Ken Aldridge, his two sons Alex and Steve, and a team of non-family executives. Aldridge’s strategy is to recruit and develop a professional, competent, and empowered work force to plan and deliver innovative solutions to challenging electrical power and transportation infrastructure projects.

The more challenging the job, the better the fit for Aldridge’s core competencies of designing and installing electrical infrastructure for large public and private clients. Major customers include airports, municipal subway and light rail transit systems, state departments of transportation, and utilities throughout the United States. Examples of their work include installation of runway lighting at major international airports, power and communications systems for transit and subway networks, transmission line and substation installations for utilities, and communication, control, and lighting for major highway systems. Many of their jobs require that they install conduit, wire, and other electrical and civil infrastructure while a subway, train, highway, or electrical substation is operating. Others require installation in areas that are very difficult to access like underneath buildings or roads, in tunnels, and through rugged and remote terrain.

Some jobs require Aldridge to win a bidding process where low cost determines the winner. In those instances, Aldridge’s ability to create innovative installation techniques allows them to complete jobs in a more efficient manner than their competitors, resulting in a higher margin at a lower price. When low price is not the most important factor, Aldridge is able to work with customers to meet their specific needs like speed of installation, safety, reliability, or specialized knowledge. In either case – low price or value add – Aldridge’s strategy of delivering innovative solutions for complex infrastructure installations makes them formidable competitors.

Feetures is a second-generation family firm that is succeeding in a completely different and highly competitive industry with a similarly well defined, clear, and focused competitive strategy. Feetures, headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, designs, markets, and distributes athletic socks nationally and internationally. Feetures continually innovates its products and marketing strategies and has built a strong brand with high customer loyalty. Their strategy is to design, contract manufacture, and market technically superior athletic socks for specific activities like running, golfing, and hiking. They distribute their socks through independent specialty retailers like running and golf shops, national sports retailers like Dick’s and Academy, and online through Amazon and their own direct-to- consumer website.

Feetures is led by Hugh Gaither, his two sons, John and Joe, and a team of non-family executives. The Feetures website (www.feetures.com) reinforces the company’s strategy with a picture of Hugh, John, and Joe, and a caption that says, “We wake up every day with the sole focus of making the best performance socks in the world.” Online product reviews indicate that customers agree Feetures is delivering on that brand promise, and that they happily pay a premium price for a technically superior athletic sock.

ALIGNMENT AND STRATEGIC FIT

Once a company adopts an overall competitive strategy, it is essential that each of its operating strategies is aligned with that overall strategy. Marketing, production, operations, service, human resources, and financial strategies must be aligned with the overall strategy to achieve strategic fit. A good competitive strategy is one that defines what a company will not do as much as it defines what it will do. It helps company leaders make strategic choices.

A good competitive strategy is one that defines what a company will not do as much as it defines what it will do.

Feetures achieves strategic fit by investing heavily in product design and marketing rather than in manufacturing. Their value add is in the innovative features built into their socks and in helping customers choose the right sock for the right activity. They contract with manufacturers around the world who meet their exacting standards to produce their socks, rather than investing in manufacturing facilities themselves. Feetures can charge premium prices because their customers are willing to pay for socks with superior fit, comfort, and wearability. They designed their website to communicate the benefits of their socks and to help customers find the right sock for their specific sport or activity. They invest heavily in social media to reach target customers with messages that drive demand for their specialty and national chain retailers and for their own direct-to-consumer channel. That all adds up to strategic fit – technically superior products, premium prices, niche marketing and distribution strategies, and investments in the activities that create value for customers.

Aldridge achieves strategic fit by investing heavily in their people, processes, and equipment. They are highly selective in who they hire and devote considerable time, effort, and resources to technical and leadership training. They know that it takes creative, well-trained people at all levels of the company to execute on their overall competitive strategy of providing innovative solutions for their customers. They have adopted an Agile planning and productivity management system designed to evolve solutions through an iterative process that relies on the collaboration of Aldridge’s cross-functional teams and their customers. They utilize forward-thinking procurement and prefabrication techniques to assemble subcomponents in their workshop, which is more efficient than trying to do everything on the job site. They engineer and assemble specialized equipment for specific tasks to facilitate faster, safer installations. They are also selective about the kinds of jobs they bid, choosing ones for which their approach adds the most value. The right people with the right training, and processes that encourage creative solutions for the right customers, are evidence that Aldridge’s human resources, operations, and business development strategies are well aligned with their overall competitive strategy.

CULTURE AND EXECUTION

Strategy, regardless of how well crafted, can produce desired results only if it is well executed. Strategy can be well executed only if the culture of the organization supports it. Management guru Peter Drucker is often remembered for his famous aphorism, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” A useful way to think of organizational culture is “the way we do things around here.”

Aldridge promotes a culture of disciplined creativity that supports its innovation strategy. The leaders at Aldridge value people in the organization who think outside the box and are constantly thinking about how something can be done rather than why it cannot be done. They refer to these people as “subject matter experts,” and allow them wide latitude to employ installation techniques that have not been tried before. They also value people who are more process oriented and rely on them to harness the creativity of the subject matter experts to achieve organizational objectives. The tension between creativity and process sometimes causes conflict. Aldridge embraces and manages that conflict to produce better solutions rather than seeking to avoid the conflict. As a result, Aldridge has gained a national reputation as a go- to contractor for the most challenging electrical infrastructure jobs.

Ken Aldridge says he learned the value of the natural conflict between creativity and discipline in working with his brother Warren. Warren is a brilliant thinker who has become a legend at Aldridge for designing and implementing installations in ways that others thought impossible. Ken instilled discipline in the organization by championing strategic planning, leadership development, and financial controls. When they were younger, those different ways of thinking often resulted in conflict between the two brothers, but over time they came to realize that it was part of the secret sauce that makes Aldridge successful. The lesson learned, and one that has permeated the culture at Aldridge, is that task- oriented conflict should be welcomed and man- aged, while relationship-oriented conflict should be recognized and resolved.

Feetures has created an enthusiastic sales and marketing-oriented culture that supports its strategy of designing technically superior athletic socks and selling them to the right customers at the right time, price, and place. Their corporate headquarters feels more like an art studio than a business office and fosters an atmosphere of creativity where innovations in design and marketing naturally evolve. The folks at Feetures delight in delighting their customers and their enthusiasm is contagious. They enjoy sharing the latest customer reviews and can tell you exactly how many pairs of socks shipped yesterday.

STRATEGY IN A FAMILY FIRM: WHAT IS DIFFERENT?

The strategic difference in a family firm is the family! This paper highlights three ways in which strategy is influenced by the business-owning family: the personal experiences and passions of family leaders, a long-term orientation, and generational transitions in leadership.

Family firms and the strategies they employ are often based on the intense personal interests and the entrepreneurial drive of their founders or later-generation family leaders, who dream of sharing their passion for something they enjoy doing with others. The products and services they provide reflect their own deep understanding of what is needed to actively engage in that interest.

Feetures founder Hugh Gaither is a long-time running enthusiast, so when he founded the company almost twenty years ago, he knew what serious runners wanted in an athletic sock. He also had 25 years of prior experience as a leader in a former sock manufacturer and had watched the industry evolve to compete primarily on price. The more successful companies were ones that could scale production to pro- duce generic athletic socks at a very low cost, but those socks did not provide the benefits run- ning enthusiasts desired. Serious runners want socks that are comfortable, prevent blisters, fit their foot like a glove, support their arches, and are durable. While it would be expensive to manufacture a sock with those features, Hugh believed that runners would pay a premium price for a sock that delivered the benefits they wanted. He also recognized that innovative de- sign and marketing were the real value adds, so he focused his effort and capital in those areas instead of investing in a manufacturing facility.

As is often the case with entrepreneurs, Hugh was advised that his idea would never work be- cause the world did not need another athletic sock, nor would he be able to compete with large low-cost sock manufacturers. Undeterred, he pursued his passion with energy, determination, and contagious enthusiasm. He was willing to invest for the long term to realize his dream and build a company that he could pass on to the next generation. Hugh’s son, John, and daughter, Catherine, helped start Feetures. When his younger son Joe was 15 years old and still in high school, he suggested the company name after overhearing a telephone conversation Hugh had with a colleague about company strategy. Feetures has been a family affair with a long-term orientation from the beginning.

Brothers John and Joe moved into senior management positions as part of the succession process at Feetures. They demonstrate how strategic shifts often occur during generational transitions in leadership in a family enterprise. While the overall strategy remains the same, Joe is driving a change in marketing strategy, and John is leading an adjustment in production strategy. As the youngest member of the leadership team, Joe has a deep understanding of social media and the power of the Internet. Several years ago, he advocated for a larger investment in Feetures’ direct-to-consumer channel. That investment has paid off handsomely as direct-to-consumer has become the fastest growing and most profitable channel for Feetures, growth that has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic as customers engage in more outdoor activities and shop from home.

While Joe is growing sales, John is changing production strategy to ensure that Feetures can keep up with increased demand and respond to potential supply chain disruptions by sourcing manufacturing from multiple manufacturers in different parts of the world, including their home state of North Carolina. While these shifts in operational strategies have been vigorously debated, they have Hugh’s full support. He is wise to listen to new ideas from the next generation who bring their own experiences and perspectives to the task of evolving strategy to respond to changes in the marketplace.

Aldridge’s focus on people and leadership development, which is so important to their innovation strategy, is based more on Ken Aldridge’s personal development as a leader than it is on a passion for electrical infrastructure, although he loves the challenges it presents as well. He was thrust into the CEO position at the age of 29 when his father unexpectedly died. He relied heavily on more experienced non-family executives in the firm to mentor and guide him and often talks about how grateful he is to those leaders who took him under their wing. Later in his career, as the company grew and became increasingly complex, he enrolled in Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People course and learned that the most effective leaders constantly work on building their own skills, developing self-awareness, and fostering positive relationships with others. The skills he learned through that training helped him deal more effectively with conflicts, including those he had with his brother who also worked in the family business. As a result of his own experiences, Ken is passionate about providing leadership and technical training opportunities for the people who work at Aldridge. He knows it is good for the business, but he is even more passionate about how it can help people make positive changes in their personal lives. This dedication to leadership development is so important that it is part of Aldridge’s overall competitive strategy statement.

Ken, Steve, and Alex Aldridge demonstrate their commitment to the long-term growth and profitability of the company when they decide to enter a new line of business or geographic market. In recent years, they have opened offices on the East and West Coasts and have added a drilling operation to their portfolio of services. They make long-term investments in hiring, training, and equipping the people needed to develop new initiatives. They also acquire businesses that already have the core competences required to compete in a new market. Those investments may hurt the bottom line in the short run, but they are designed to improve profitability over time. Next quarter’s earnings matter, but not as much as building long-term value in the business.

The generational shift in strategy at Aldridge is also evident as Alex and Steve have moved into senior leadership positions, and Ken has transitioned from the CEO to the Chairman role. Alex and Steve have focused their leadership team on preparing for the opportunities and challenges created for Aldridge as the country moves toward more reliance on renewable energy and develops “smart” highways. While the overall competitive strategy remains the same, those industry trends have major implications for operating and business development strategies going forward.

STRATEGIC PLANNING: KEEP IT SIMPLE

SWOT Analysis

When creating a strategic plan designed to achieve company goals, define an overall competitive strategy, and execute on that strategy, keep it simple. One book on strategic planning for the family business suggests a process that includes choosing among 27 different strategic options. That approach makes strategic planning overly complex, and we are unaware of any family firms that employ that method.

An effective strategic planning process begins with an analysis of the external environment and the internal capabilities of the family enterprise. A simple but powerful exercise is to conduct a SWOT analysis (see Figure 1), a technique developed by Albert Humphrey at the Stanford Research Institute in the 1960s. A SWOT analysis involves identifying a firm’s internal strengths (S) and weaknesses (W), and the opportunities (O) and threats (T) presented by the external environment in which it operates. A SWOT analysis encourages thinking about these questions: What strengths can you build on to further develop or create core competitive competencies?

- Are there any weaknesses in your organization that need to be addressed?

- Do you perceive external threats from competitors, changes in your industry or markets, or general economic conditions?

- Do you see opportunities for attracting new customers for your existing products or services, creating new products or services, or entering new markets?

- Are there performance gaps in the execution of your current strategy that need to be closed before you pursue new opportunities?

A SWOT analysis is useful for developing the overall competitive strategy of the firm and for identifying the specific marketing, operations, human resource, financial, and other function- specific operating strategies designed to execute that overall strategy. Firms that do a good job with strategic planning usually conduct this kind of analysis on an annual basis to test the current validity of the overall competitive strategy, which tends to stay relatively stable over time, and to adjust operating strategies in the functional areas of the business to respond to changes in the external environment. It is a simple process, but one that encourages regular reflection about how the increasingly rapid changes in today’s marketplace of ideas, products, and services might affect the business.

A good SWOT analysis includes an assessment of competitors. Are your competitors developing strengths that represent a threat to your business? Do they have weaknesses you can exploit? Are they pursuing opportunities that you need to consider? How are they responding to the threats you pose to them? Why do current or potential customers prefer to do business with you rather than with your competitors, and how do you ensure that your customers will continue to favor your products and services?

Keep in mind one caveat in using a SWOT analysis. When experiencing unfavorable business results, it is tempting to chase new opportunities. Before succumbing to this temptation, determine if the problem is with execution of the current strategy or with the strategy itself. Creative entrepreneurs often find that chasing the newest opportunity is a lot more fun than devoting energy to improving current operations. The very best firms are ambidextrous (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). They are skilled at closing performance gaps and pursuing new opportunities at the same time.

Putting It All Together

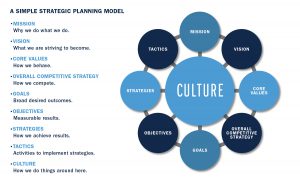

How can family firm leaders incorporate deep strategic thinking into a strategic plan that provides clear direction for an entire organization? A simple but effective method is depicted in Figure 2. The process starts with defining a clear mission and then proceeds clockwise around the model, with one step leading to the next until very specific tactics designed to implement operating strategies and the overall competitive strategy are identified. Culture is depicted in the center of the model since it is central to an organization’s ability to execute on its strategy. Overall competitive strategy and culture are highlighted in red text because they are reflections of deep strategic thinking and are often missing elements of strategic plans.

Definitions of Strategic Planning Terms

Mission: A mission statement is a concise expression of an organization’s overall purpose. It answers the question, “Why do we do what we do?” For a family business, it speaks to the way in which the company provides value to its stake- holders, including customers, employees, family owners, and the community in which it operates.

Vision: A vision statement paints a picture of the desired future state of the organization. It answers the question, “What are we striving to become?” Research on family businesses suggests that a key reason family firms succeed through multiple generations of family ownership is because family owners share a common vision for the future of the family enterprise.

Core Values: Values articulate the behaviors expected of everyone involved in the family enterprise. It answers the question, “How do we behave?” When identifying and communicating core values, it is important to define each of those values, since the words used to express values can mean different things to different people. For example, the owners of one family firm define integrity as being honest, fair, and transparent in all their interactions, following through on commitments, taking responsibility for their actions, and modeling that behavior to their children.

Overall Competitive Strategy: An overall competitive strategy is “a company’s distinctive approach to competing” Porter (1996). It answers the question, “How do we compete?” It explains why a customer would prefer to buy a firm’s products and services instead of a competitor’s.

Goals: Goals are broad statements of what a strategic plan is designed to accomplish. They answer the question, “What are our desired out- comes?” For a family business, there are usually family, ownership, and business goals. It is critical for those goals to be aligned.

Objectives: Objectives are measurable results. They answer the question, “Are we achieving our goals?” What gets measured gets done, so goals without measures can be meaningless words on paper. It is not unusual for leaders to think that the only outcomes that can be measured are financial but almost any goal, including customer and employee perceptions, can be measured.

Operating Strategies: Operating strategies de- fine the initiatives a family firm will undertake to implement the overall competitive strategy. They answer the question, “How do we achieve our desired results?” Strategies should be developed for each of the major functional areas of the business and they should be aligned with each other.

Tactics: Tactics are the specific activities undertaken in each of the functional areas of the business to carry out each strategy. They answer the question, “What will we do to implement our strategies?” Tactics are what customers, employees, and other stakeholders see, do, or experience as a family business carries out its strategies. When carefully planned and thoughtfully executed, tactics reinforce the overall competitive strategy.

Culture: Culture defines what people inside and outside the family business experience when they interact with each other and how that experience makes them feel. It answers the question, “How do we do things around here?” The culture should support the overall competitive strategy and the leaders must model the desired behaviors to successfully implement that strategy.

Review and Re-planning

Mission, vision, core values, overall competitive strategy, and culture tend to stay relatively stable over time. Goals, objectives, operating strategies, and tactics can be long term or short term depending on the nature of the goals and the pace of change in the external environment or industry in which a family firm operates. What is short term for a family business in a relatively stable industry may be long term for a family firm in a fast-changing industry like technology. Whatever the nature of the business, it is important to review the strategic plan on a regular basis, at least annually, and more often if the business environment changes rapidly or an un- expected event presents new threats or opportunities for the business. Regularly reviewing the plan to keep it up to date increases the likelihood that management will use the strategic plan as a guide for decision making, resource allocation, creation of annual business plans and budgets, and maintaining focus on execution of the competitive strategy. Too many strategic plans sit on bookshelves gathering dust and have little effect on the actual operation of the business.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Strategy is not that complicated but getting strategy right is hard. It requires making tradeoffs among strategic options and defines what an organization will not do as much as what it will do. Deep strategic thinking informed by an under- standing of a firm’s internal and external environments, customers, core competencies, and owner goals fosters the development of a competitive strategy that infuses a family enterprise with purpose, direction, and energy.

Family business leaders who are skilled in strategic thinking understand that creating and nurturing a culture that supports the firm’s overall competitive strategy is one of their most important leadership tasks. They also under- stand that the process of creating strategy is more important than the actual plan itself, as it provides an opportunity for leaders to get crystal clear about how they will compete and what they should do when things do not turn out exactly as planned. Dwight D. Eisenhower led the Allied Forces to victory in World War II and was a brilliant strategic thinker. He famously said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

Strategic thinking is deciding how to compete. Strategic planning is a continuous process of learning how to achieve business and family goals. Family firms that get strategy right enhance their opportunity to prosper through multiple generations of family ownership. The leaders at Aldridge Electric and Feetures understand that, and as a result, they are enjoying success in highly competitive markets.

REFERENCES

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard business review, 74(6), 61-78.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press.

Raisch, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management, 34(3), 375-409.doi:10.1177/0149206308316058

Steve Miller is a family business expert, co-founder of the Family Enterprise Center at UNC Kenan-Flagler, and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior. His research focuses on next-generation leadership development in family-owned enterprises.

Steve works with family businesses and his students to help them create world-class, sustainable enterprises. His approach is to collaborate with family business leaders to develop and employ strategies designed to align business, family, and ownership goals. He draws on his 35 years of experience as the top non-family executive of the Vanderbilt/Cecil family- owned Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C., where he played a key role in making Biltmore the most visited historic home in the United States, with over one million visitors each year.

Steve also is president of GenSpan, Inc. in Asheville, NC. In that role, he consults on succession planning, leadership training, and strategy for The Biltmore Company and a number of other large family business clients. Steve has extensive board experience and currently serves as chairman of the board of Draper & Kramer, a family-owned real-estate development and management firm in Chicago and as a board member of Riverbend Malt House in Asheville, N.C., which malts grains for craft brewers and distillers.

Professor Miller earned his PhD in Management – Designing Sustainable Systems at Case Western Reserve University. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the Undergraduate Business Program at UNC Kenan-Flagler and completed the Advanced Management Program at Harvard Business School.